Mozi

Discovered in 2019, Mozi is a P2P botnet using the DHT protocol that spreads via Telnet with weak passwords and known exploits. Evolved from the source code of several known malware families; Gafgyt, Mirai and IoT Reaper, Mozi is capable of DDoS attacks, data exfiltration and command or payload execution. The malware targets IoT devices, predominantly routers and DVRs that are either unpatched or have weak telnet passwords. In a report from IBM, Mozi accounted for 90% of IoT network traffic between October 2019 and June 2020.

Below is a table of the most common vulnerabilities Mozi exploits to grow the botnet.

| Vulnerability | Affected Aevice |

|---|---|

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/40740 | Eir D1000 Router |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/6864/ | Vacron NVR devices |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/37169/ | Devices using the Realtek SDK |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/41598/ | Netgear R7000 and R6400 |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/43055 | DGN1000 Netgear routers |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/41471/ | MVPower DVR |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/43414/ | Huawei Router HG532 |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/37171/ | D-Link Devices |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/44576/ | GPON Routers |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/28333/ | D-Link Devices |

| https://www.exploit-db.com/exploits/39596/ | CCTV DVR |

The Mozi botnet is comprised of nodes that utilize a distributed hash table (DHT) for communication. These nodes also host the Mozi.m and Mozi.a malware binary files, passed during the compromise of new hosts, on a randomly chosen port. Using DHT allows the malware to bypass the use of standard malware command and control servers while hiding behind the large amount of typical DHT traffic. In a benign use case, the standard DHT protocol is commonly used to store node contact information for torrent and other P2P clients.

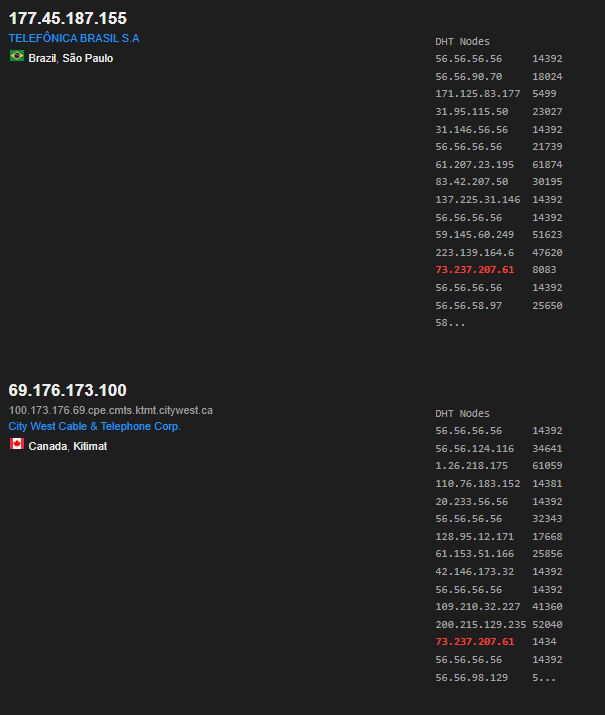

An example of what this may look like can be seen from Shodan. I searched the IP and although there wasn’t a direct result of the IP, it was included in the DHT table of five bootstrap nodes. These bootstrap nodes are used to guide new nodes to join the DHT network. Everything in the DHT Nodes list are botnets that report to the bootstrap node.

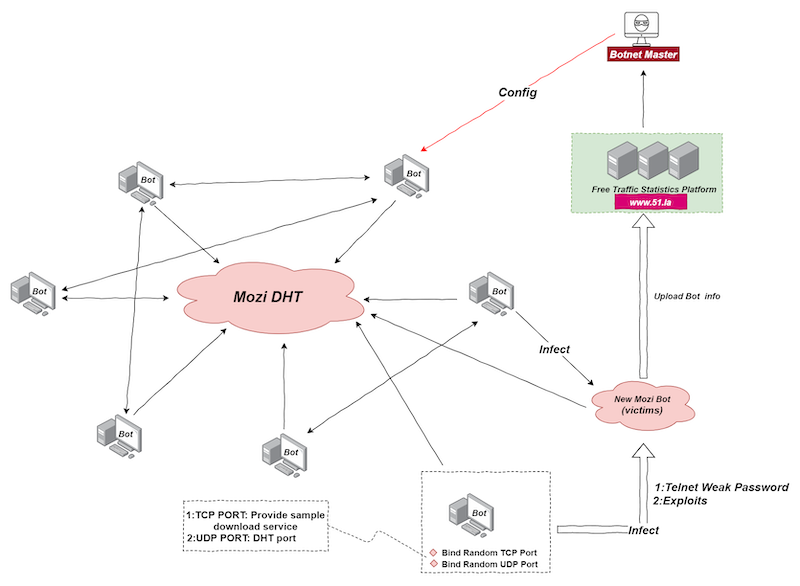

The network diagram below explains how the botnet operates. The Botnet Master distributes a payload called Config which issues instructions for each node. Individual bots start HTTP services on random local ports to provide sample downloads or receive them from an address in the Config file. The bot then logs in to a target with a weak password or uses a vulnerability exploit and downloads a sample. The Mozi Bot sample is then run on the victim device and joined to the P2P network where it becomes a new node and carries out infections to more victims.

Malicious Page

Looking at latest submissions from URLhaus, I clicked a recent Mozi submission that was still online. The reason for clicking this was nothing more than picking a random item from a list. As I was testing the Greynoise API, I decided to submit this to the IP Timeline Hourly Summary endpoint just to see if I’d get a response. What caught my attention was it returned http_paths: [”/boaform/admin/formLogin”]. A simple assumption could be impersonating a themed landing page attempting to grab user credentials, but Mozi doesn’t create landing pages to phish user credentials. Something else must be going on here. So I ran a separate GreyNoise query to find if other hosts have this path included and to my surprise, the query returned 55,488 results. This is too much noise to simply search through so I had to think of a different method. I switched to VirusTotal and did a simple search for /boaform/admin/formLogin which returned 277 files. Now we’re getting somewhere. This is still a lot to go through, but Mozi samples are either named Mozi.m or Mozi.a which helped narrow the scope of files to look at. Again with no reasoning, I clicked on the first file I saw named Mozi.m and looked at the Relations tab to see what the malware connects to. There was a common pattern amongst the URLs that included ?username=<something>&psd=<something>. Something being admin, user, ec8, or adminisp. So in order to access whatever was hosted here, a username and password must be supplied in the URL. One issue I noticed is these all returned either 400, 403, 404, or 503 error codes. As mentioned above, Mozi hosts binary files on a randomly chosen port. Cool, so to get this file, I’d have to know the port it’s hosted on. Luckily, the URLHaus submission showed a file is downloaded from that IP on port 48824, so I’ll test that first. The second issue was I had to know what user:pass this server accepted. A few failed attempts later, I found it was user:user because Chrome immediately warned me I’m downloading malware. Great!

hxxp://73.237.207[.]61:48824/boaform/admin/formLogin?username=user&psd=user

Mozi Sample

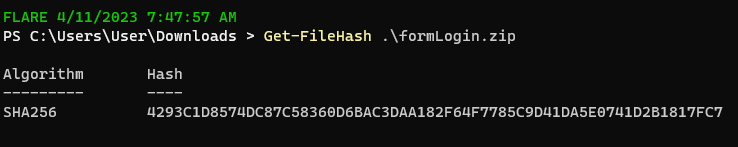

By now, you may be wondering why I did all this work when I could’ve just downloaded the sample found on URLhaus. The file came from hxxp://73.237.207[.]61:48824/i and the payload is on VirusTotal. When I downloaded formLogin.zip, the hash even matched with the VirusTotal submission.

I went through all that work above because the file path had to have some importance, otherwise it wouldn’t be included in 55k results. I wanted to figure out what is was used for and rabbit holes are fun. As for why this IP hosts both /i and /boaform/admin/formLogin?username=user&psd=user yet downloads the same payload with different file names, I’m not sure. The /boaform/admin/formLogin is a router endpoint that was susceptible to a number of CVEs given the device kept default or easily bruteforced credentials. In this case, it appears this host was vulnerable to CVE-2017-17215. A similar exploit using the same endpoint appeared a few years later. CVE-2022-30023 is an authenticated command injection vulnerability on Tenda HG9 routers.

Anyway, back to the task at hand.

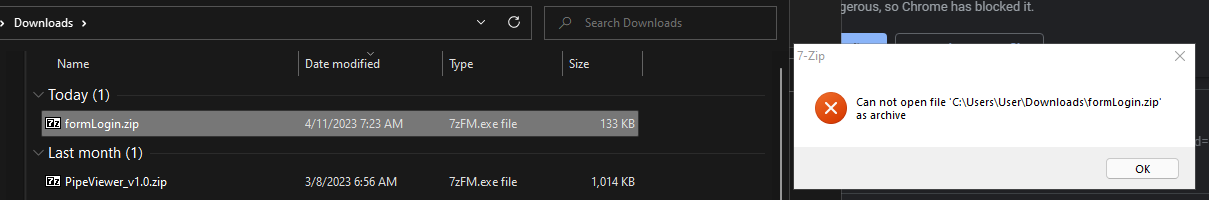

The URL downloads formLogin.zip which apparently cannot open as an archive. Weird.

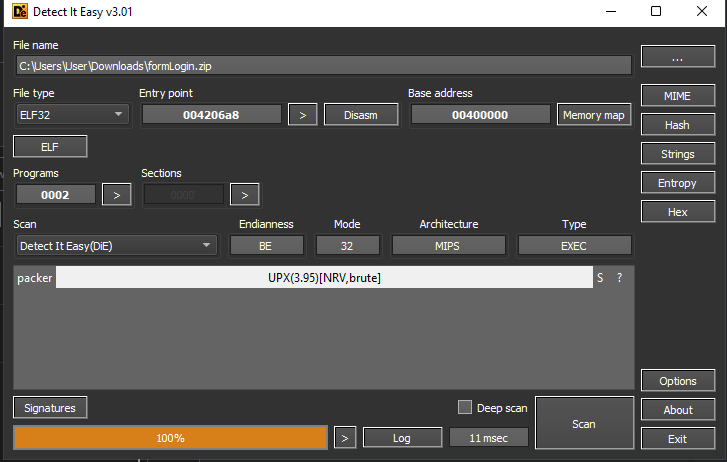

To get more information, I opened with ZIP in Detect It Easy and had my answer. The sample is packed with UPX.

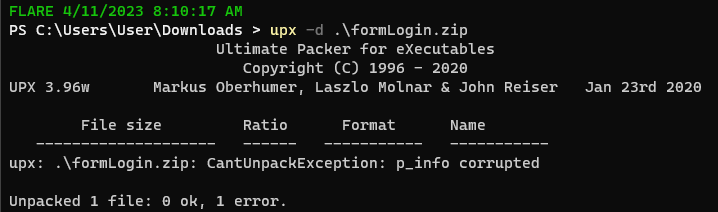

In a perfect world, you could just unpack a UPX packed binary by running upx -d <file> -o <fileUnpack>. But this isn’t a perfect world and Mozi isn’t simple. However, it is widely known and luckily a tool exists to specifically unpack and decode Mozi samples.

Mozitools

When I tried to unpack the sample using the command mentioned above, I got an error about the p_info structure.

So what does p_info have to do with this? Well UPX adds two headers when packing; l_info and p_info. Within p_info are three variables; p_progid, p_filesize, and p_blocksize. Mozi developers overwrote the latter two variables with null bytes to avoid simply unpacking with UPX.

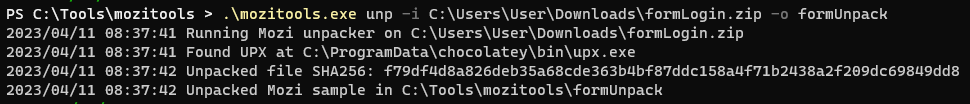

Mozitools can fix this by repairing the p_info structure which then allows unpacking.

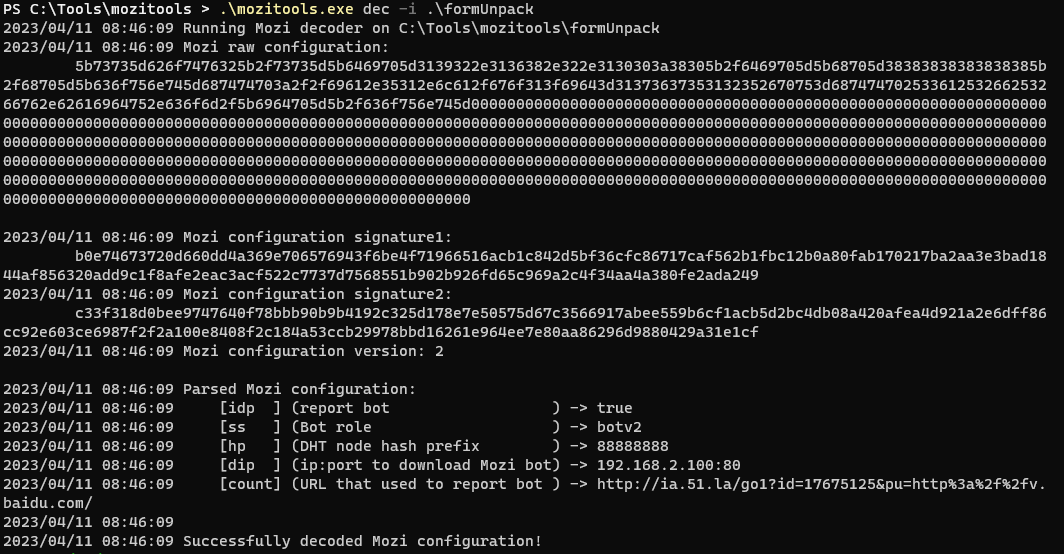

However, we aren’t done here. The sample is unpacked, but still encoded. The second feature of Mozitools decodes the configuration by supplying a hardcoded XOR key 4E665A8F80C8AC238DAC4706D54F6F7E found in the unpacked sample. After, Mozi queries other nodes through the DHT protocol to obtain newer configurations if they exist.

The URL within the configuration returns a 200 OK but I didn’t get any data besides that. The reason being www.ia.51.la is a traffic statistics platform that new Mozi bots (victims) report to which then reports to the bot master.

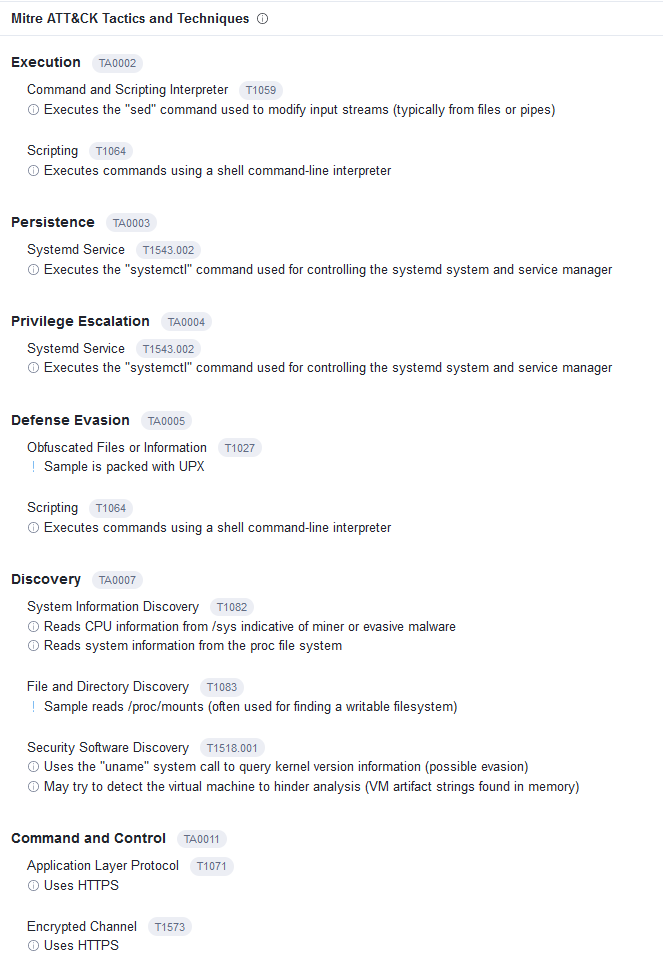

As a final check, I opened the sample in HxD and saw the .ELF file header which matches with the uploaded VT sample. Now with an unpacked and decoded sample, it can be uploaded to sandboxes to reveal behaviors and more indicators.

Conclusion

I ended up learning a lot more about Mozi than intended. Initially, I was just interested in figuring out what that endpoint was responsible for. After enough pivoting, it was revealed the endpoint is common on various routers and Mozi finds which ones are vulnerable to command injection in order to grow their Botnet infrastructure. With GreyNoise showing over 55k results, 31k being malicious, it’s safe to assume the Botnet continues to grow larger every day with no signs of slowing down.

References

https://kn0wledge.fr/projects/mozitools/

https://blog.netlab.360.com/mozi-another-botnet-using-dht/

https://urlhaus.abuse.ch/url/2605065/

https://securityintelligence.com/posts/botnet-attack-mozi-mozied-into-town/